Concrete is a widely used building material that offers several significant advantages as well as some notable disadvantages.concrete is regarded for its remarkable adaptability, durability, and versatility, making it one of the most essential materials in contemporary building.

Concrete has shown to be a key component of structural innovation in everything from tall skyscrapers to underground tunnels, from enormous dams to complex architectural designs. It is a preferred material for both engineers and architects due to its ability to be formed into almost any shape, long-term strength, and resilience to environmental influences.

When deciding if concrete is appropriate for a certain project, it is important to take into account its unique combination of benefits and drawbacks, just like any other material. We examine the main advantages and disadvantages of utilising concrete in construction below.

Advantages of Concrete

1. Economic Benefits

2. Superior Compressive Strength

3. Versatility in Molding and Shaping

4. Synergy with Steel Reinforcement

5. Advanced Repair Capabilities

6. Efficient Placement Methods

7. Exceptional Durability and Fire Protection

Economic Benefits

- Economic benefits of concrete in construction primarily stem from its cost-effectiveness, availability, and durability.

- Concrete’s raw materials such as cement, water, aggregates are abundant and affordable, which helps reduce initial material costs.

- Concrete structures generally require less maintenance and repair over time, yielding savings throughout the structure’s lifespan.

- Its strength allows for economical designs that can carry heavy loads using relatively less material compared to alternatives.

- Efficient placement and curing methods also speed construction timelines, further reducing labor and equipment expenses.

Economic benefits

- Large-scale concrete pouring operations demonstrating efficient use of equipment and labor.

- Concrete roads and infrastructure lasting many years with minimal repair.

- Modular precast concrete elements saving time and expense on site.

- Mass concrete foundations providing stable, cost-effective bases for buildings.

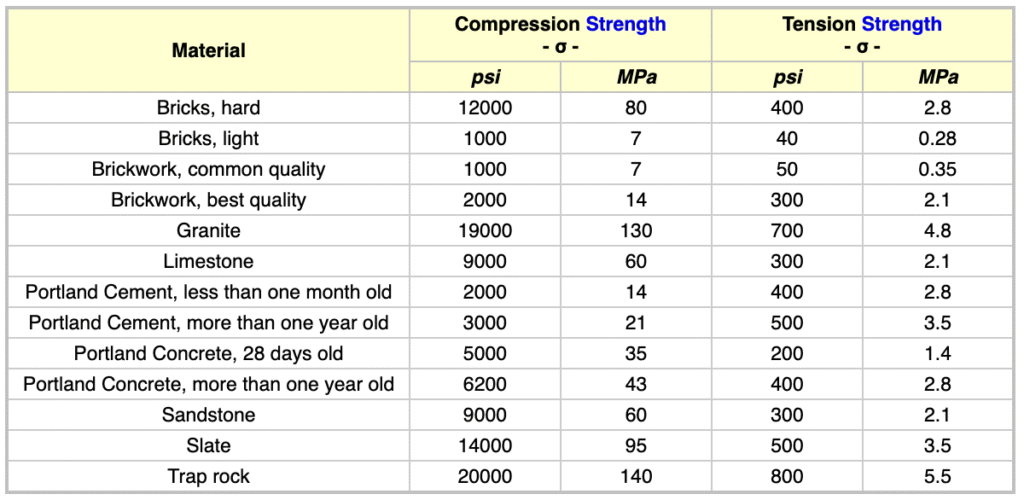

Superior Compressive Strength

Concrete is renowned for its superior compressive strength, which is its ability to withstand loads that tend to reduce its size by pressing it together.

This property is fundamental in construction, allowing concrete to support heavy structural loads in buildings, bridges, pavements, and other infrastructure.

Compressive strength is typically measured in pounds per square inch (psi) or megapascals (MPa) by testing cylindrical or cubic specimens of concrete in a compression testing machine.

Standard tests are conducted after 7 days and 28 days of curing, with the 28-day strength being the primary benchmark for structural design.

Typical compressive strength values:

- Residential concrete: 2,500 to 4,000 psi

- Structural concrete for bridges, beams: 3,500 to 5,000 psi

- High-performance concrete: above 5,000 psi

- Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC): up to 30,000-50,000 psi

Concrete achieves this strength due to the chemical reaction between cement and water (hydration) forming strong calcium silicate hydrates that bind the aggregates into a solid mass. It excels in compression but is weak in tension, which is why steel reinforcement is used alongside it in reinforced concrete.

compressive strength benefits

- Concrete specimens undergoing compression tests inside machines.

- Close-ups of hardened concrete microstructure.

- Graphs of strength development over curing time.

- Visual comparison between regular and ultra-high performance concrete strength.

These visuals help demonstrate why concrete is favored for load-bearing applications with its reliable, high compressive strength.

Versatility in Molding and Shaping

Concrete offers extraordinary versatility in molding and shaping, making it a preferred material for diverse architectural and structural designs.

This versatility arises because concrete begins as a fluid mixture that can be poured or cast into any shape before hardening into a solid mass.

The mold or formwork used defines the final shape and texture of the concrete element.

- Custom Forms and Molds: Concrete can be shaped using custom-built molds made from materials such as wood, metal, plastic, fiberglass, or fabric. This allows for a wide variety of shapes from simple slabs and columns to complex architectural features and sculptures.

- Traditional to Innovative Formwork: Traditional plywood and lumber forms are inexpensive and adaptable for basic structures, while metal and plastic forms provide durability and reuse for repetitive shapes. Fabric molds enable organic, flowing shapes rarely achievable with rigid forms.

- Surface Finishes: Different mold materials and techniques can produce various textures and finishes from smooth polished surfaces to exposed aggregate effects.

- Adaptability for Complex Projects: Complex molds can accommodate curves, angles, recesses, and projections, making concrete suitable for ornamental facades, countertops, stairs, and infrastructure components.

Examples of Concrete Molding Techniques

- Hand-built wooden molds for foundations and walls.

- Fabric formwork stretched over frames to create organic curves.

- Metal molds for precast concrete products like beams and panels.

- Flexible rubber molds for decorative concrete casting.

This adaptability in molding and shaping gives concrete a unique advantage in construction, enabling creativity without compromising strength.

Synergy with Steel Reinforcement

The synergy between concrete and steel reinforcement is a cornerstone of modern construction, combining the best properties of both materials to create extremely strong, durable, and versatile structures.

Key Points on Synergy with Steel Reinforcement

- Complementary Strengths: Concrete has excellent compressive strength but weak tensile strength. Steel provides high tensile strength, compensating for concrete’s weakness under tension. This combination enables concrete to withstand a wider range of structural stresses without failure.

- Bonding and Load Distribution: Steel bars (rebar) are embedded in wet concrete, where a strong mechanical and chemical bond forms as the concrete cures. This bond ensures that concrete and steel deform together, distributing loads evenly and preventing cracks from widening.

- Improved Ductility and Toughness: Steel reinforcement enhances the ductility of concrete, allowing structures to bend and deform without collapsing, which is vital in seismic and dynamic load conditions.

- Prevention of Crack Propagation: Reinforcement holds cracked concrete sections together, maintaining structural integrity and preventing further deterioration.

- Wide Applications: This synergy is essential in bridges, skyscrapers, tunnels, dams, and many other infrastructures, where strength, durability, and safety are critical.

- Construction Efficiency: Steel reinforcement allows for longer spans, more slender structures, and complex architectural shapes while maintaining strength and safety.

The blend of concrete’s compressive strength with steel’s tensile capacity results in reinforced concrete structures that are robust, long-lasting, and adaptable to diverse construction needs.

This synergy has revolutionized the building industry, enabling the construction of everything from massive bridges to earthquake-resistant buildings.

Advanced Repair Capabilities

Concrete’s advanced repair capabilities make it a highly sustainable and cost-effective material over the long term.

Various modern techniques allow for effective restoration of damaged concrete, maintaining structural integrity and prolonging service life.

Key Techniques

- Epoxy Injection: This method involves injecting epoxy resin into cracks under pressure to bond the split sections together. It restores strength and prevents crack propagation with minimal surface disruption. Epoxy bonds strongly and provides long-lasting repair, ideal for structural cracks.

- Sandjacking: A method to lift and stabilize settled concrete slabs by injecting a mix of sand, cement, and additives underneath. It fills voids and restores level surfaces while being environmentally friendly and durable.

- Polyurethane Foam Lifting (Polyjacking): Involves injecting lightweight, expanding polyurethane foam beneath sunken concrete to lift slabs quickly. It sets rapidly, allowing repaired areas to be used soon after treatment.

- Concrete Cancer Repair: When steel reinforcement corrodes inside concrete, the affected concrete is removed, steel treated or replaced, and then repaired with high-quality mortar. This stops deterioration and restores integrity.

- Surface Restoration: Techniques such as resurfacing, grinding, and membrane applications restore concrete surfaces aesthetically and functionally, sealing cracks and preventing further damage.

Benefits

- Maintain structural safety and performance.

- Economical alternative to full replacement.

- Minimal disruption with some advanced techniques.

- Environmentally friendly options like sandjacking.

- Extend the lifespan of concrete infrastructure.

Modern concrete repair innovations like self-healing concrete and robotic leveling also represent future trends enhancing repair capabilities and sustainability in construction.

Efficient Placement Methods

Concrete placement efficiency is critical for structural quality, durability, and construction speed. Various methods and practices have been developed to ensure smooth, economical, and reliable placement of concrete in different construction scenarios.

Key Methods and Practices

- Pumping and Pipeline Method: Concrete is pumped through pipes to the placement site using concrete pumps. This method is reliable for underwater works, high rise buildings, bridges, and tunnels. It reduces manual labor and allows precise placement in hard-to-reach areas. Pipeline diameter is selected based on placement height and distance to maintain flow and prevent segregation.

- Tremie Method: Used mainly for underwater placements where concrete is delivered through a vertical pipe with a funnel top. The pipe’s bottom is kept immersed in fresh concrete to avoid mixing with water, ensuring high quality and uniform placing.

- Bottom Dump Bucket Method: Used for underwater concrete, where concrete is transported in buckets lowered to the placement location and released. Suitable for large volume pours in water.

- Slip Forming: A continuous concrete pouring technique where the formwork moves vertically or horizontally during placing, ideal for tall or long structures such as silos, chimneys, and pavements. It speeds up placement and consolidates concrete uniformly.

- Shotcrete (Guniting): Concrete is sprayed pneumatically onto surfaces for repair or thin structural layers, reducing formwork needs and allowing quick placement on irregular surfaces.

- Layered Placement: Large pours like dams require placing concrete in horizontal layers with appropriate thickness and bonding techniques to prevent weak cold joints, maintaining uniform strength across the structure.

- Plan and prepare equipment, formwork, and site for smooth concrete flow.

- Place concrete within 30 minutes of batching to avoid premature hardening.

- Use tools like chutes, buckets, and pumps to minimize concrete travel distance.

- Control environmental factors such as temperature and humidity to improve curing.

- Avoid segregation by ensuring proper concrete mix design and careful handling.

These efficient methods ensure quality, minimize labor costs, and increase the speed of construction while maintaining concrete’s structural properties.

Exceptional Durability and Fire Protection

Concrete’s durability stems from its dense microstructure and chemical stability. When properly designed and placed, concrete structures require minimal maintenance compared to steel or wood alternatives.

- The material’s inherent fire resistance is particularly valuable concrete maintains its structural integrity at temperatures up to 1,500°F (816°C) for several hours, providing crucial time for evacuation during fires.

- These advantages have made concrete the world’s most widely used construction material, with annual global production exceeding 10 billion tons.

- The material’s versatility, combined with ongoing technological advances in mix design and placement methods, ensures its continued dominance in construction for the foreseeable future.

Disadvantages of Concrete

1. Low Tensile Strength

2. Shrinkage and Expansion

3. Thermal Movement

4. The Creep Phenomenon

5. Moisture-Related Vulnerabilities

6. Chemical Attack Susceptibility

7. Seismic Design Challenges ( Lack of Ductility)

Low Tensile Strength

While concrete excels in compression, its tensile strength typically ranges only between 8-12% of its compressive strength.

This fundamental weakness necessitates careful engineering solutions. Modern construction addresses this through various reinforcement techniques: steel reinforcement bars (rebar) that can withstand tensions of 40,000-60,000 psi, fiber reinforcement using steel, glass, or synthetic fibers, and prestressing techniques that introduce compressive forces to counteract tensile stresses.

Without proper reinforcement, a concrete beam spanning just a few meters could crack under its own weight, making this limitation a critical consideration in structural design.

Shrinkage and Expansion

The dynamic nature of concrete’s volume presents significant engineering challenges. During the initial curing period, concrete typically shrinks by 0.4 to 0.8 millimeters per meter.

Environmental exposure causes further dimensional changes: drying shrinkage can continue for months or years, while moisture absorption can cause expansion of up to 0.2%.

These movements necessitate carefully designed construction joints every 20-30 meters in large structures. The Hoover Dam, for example, required extensive joint systems and was poured in individual blocks to manage these volume changes effectively.

Thermal Movement

Concrete’s thermal expansion coefficient (approximately 10×10⁻⁶/°C) means significant movement in large structures. A 100-meter concrete beam can expand or contract by up to 12mm with a 10°C temperature change.

Bridge decks may move several centimeters between summer and winter. Without proper expansion joints, thermal stresses can cause severe cracking and structural damage.

Modern designs incorporate expansion joints every 30-40 meters in buildings and bridges to accommodate these movements safely.

The Creep Phenomenon

Under sustained loading, concrete exhibits creep – continuous deformation over time. This behavior can have serious implications: long-term deflections can be 2-3 times the initial elastic deformation, prestressed concrete structures may lose 15-25% of their initial prestress force, and tall buildings can experience several centimeters of shortening due to creep.

Engineers must account for creep in their designs, particularly in prestressed structures and tall buildings where its effects are most pronounced.

Moisture-Related Vulnerabilities

Despite its solid appearance, concrete contains a network of microscopic pores that allow moisture movement. Water can penetrate up to several centimeters in standard concrete.

This permeability can lead to: reinforcement corrosion in marine environments, freeze-thaw damage in cold climates, efflorescence (white deposits) on surfaces, and reduced structural durability.

Modern solutions include waterproofing admixtures and surface treatments, but complete impermeability remains challenging to achieve.

Chemical Attack Susceptibility

Concrete’s vulnerability to chemical attack poses significant durability concerns. Sulfate attacks can cause expansion and cracking, while alkali-aggregate reactions can lead to internal structural damage.

Acid rain in urban environments can gradually erode exposed surfaces, and marine environments pose particular challenges due to chloride penetration. The annual cost of chemical-related concrete deterioration in infrastructure exceeds billions of dollars globally.

Seismic Design Challenges ( Lack of Ductility)

Concrete’s brittle nature presents particular challenges in earthquake-prone regions. Sudden failure can occur without warning, with limited ability to absorb seismic energy.

This requires complex reinforcement details for ductile behavior and higher construction costs in seismic zones. Modern seismic design codes require extensive detailing and special reinforcement configurations to ensure adequate performance during earthquakes.

Advantages of Reinforced Cement Concrete (RCC)

1. Strength and Durability

2. Design Versatility

3. Fire and Weather Resistance

4. Economic Efficiency

5. Seismic Performance

6. Structural Integration

7. Maintenance Optimization

8. Environmental Adaptability

Strength and Durability

- At the heart of modern construction, RCC stands as a testament to engineering innovation, combining the compressive might of concrete with the tensile strength of steel.

- This synergy creates structures that can withstand immense loads while maintaining their integrity for decades. Modern RCC structures routinely achieve compressive strengths exceeding 6,000 psi, while the strategic placement of steel reinforcement addresses concrete’s inherent tensile limitations.

- The Burj Khalifa, soaring to heights previously deemed impossible, exemplifies this strength, utilizing high-performance RCC that maintains its structural integrity despite Dubai’s harsh desert environment and enormous gravitational loads.

Design Versatility

- RCC’s remarkable adaptability transforms architectural visions into reality. Unlike traditional building materials, RCC can be molded into virtually any shape while maintaining its structural integrity.

- The Sydney Opera House’s iconic shells, once considered unbuildable, showcase RCC’s ability to achieve complex geometries. This versatility extends beyond aesthetics architects and engineers can seamlessly integrate structural elements, from delicate shells to massive columns, creating buildings that are both beautiful and functional.

- The material’s plasticity in its fresh state allows for continuous, monolithic construction, enabling the creation of structures with flowing, organic forms that would be impossible with other materials.

Fire and Weather Resistance

- The robust nature of RCC provides exceptional protection against environmental challenges. When exposed to fire, RCC maintains its structural integrity at temperatures up to 1,500°F (816°C), significantly outperforming unprotected steel structures.

- The Pentagon’s RCC construction demonstrated this resilience during the September 11 attacks, where its fire resistance prevented catastrophic structural failure.

- Beyond fire protection, RCC excels in weathering resistance, standing strong against decades of rain, snow, and UV exposure. The concrete cover protects internal steel reinforcement from corrosion, while the dense concrete matrix resists degradation from normal environmental exposure

Economic Efficiency

- While initial construction costs may be higher compared to some alternatives, RCC’s long-term economic benefits are substantial. Studies consistently show that RCC buildings can reduce lifetime costs by 30-50% compared to equivalent steel structures.

- This economy stems from minimal maintenance requirements, lower insurance premiums due to superior fire resistance, and extraordinary durability that can exceed 100 years with proper design.

- The reduction in maintenance and replacement costs, combined with the material’s longevity, makes RCC particularly attractive for large-scale infrastructure projects where long-term performance is crucial.

Seismic Performance

- Modern RCC design incorporates sophisticated features that provide exceptional earthquake resistance. Through carefully detailed reinforcement patterns, RCC structures can exhibit ductile behavior during seismic events, absorbing and dissipating energy that would otherwise cause catastrophic failure.

- The Taipei 101 skyscraper stands as a testament to these capabilities, incorporating advanced RCC design to withstand frequent seismic activity. The material’s mass and rigidity, combined with proper reinforcement detailing, allow structures to redistribute loads during earthquakes, preventing progressive collapse and protecting occupants.

Structural Integration

- The composite action between concrete and steel in RCC creates a remarkably efficient structural system. The concrete’s excellent compressive strength works in perfect harmony with steel’s superior tensile properties, while the bond between these materials ensures they act as a unified system under loading.

- This integration allows for longer spans and taller structures than ever before possible. Additionally, the similar thermal expansion coefficients of concrete and steel (approximately 10 × 10⁻⁶/°C) prevent internal stresses during temperature changes, ensuring long-term durability and structural integrity.

Maintenance Optimization

- RCC structures demonstrate remarkable resilience with minimal maintenance requirements. The concrete matrix naturally protects embedded steel reinforcement from corrosion when properly designed and constructed.

- Minor cracks can often self-heal through continued hydration and carbonation processes, while the material’s inherent durability resists deterioration from normal use.

- The Pantheon in Rome, though built with an early form of concrete, demonstrates the potential longevity of well-designed concrete structures, standing for nearly two millennia with minimal maintenance.

Environmental Adaptability

- RCC’s versatility extends to its performance across diverse environmental conditions. From the freezing temperatures of Arctic research stations to the scorching heat of desert skyscrapers, RCC can be engineered to withstand extreme conditions.

- The material’s thermal mass helps regulate interior temperatures, reducing energy consumption in buildings. Additionally, modern RCC mixtures can incorporate recycled materials and industrial byproducts, contributing to sustainability goals while maintaining high performance standards.

Key Disadvantages of Reinforced Cement Concrete (RCC)

1. High Initial Cost

2. Weight Considerations

3. Time-Intensive Construction Process

4. Reinforcement Corrosion Issues

5. Complex Repair Requirements

6. Shrinkage and Cracking Concerns

7. Environmental Considerations

7. Environmental Considerations

High Initial Cost

- The incorporation of steel reinforcement in RCC structures presents a significant financial challenge, particularly in the initial stages of construction.

- The cost of steel reinforcement can constitute up to 30-40% of the total structural cost. This substantial upfront investment makes RCC less viable for smaller-scale projects or those with limited budgets.

- The cost implications extend beyond just the materials, including specialized labor, quality control measures, and precise engineering requirements.

- While the long-term benefits often justify this investment for larger projects, the initial financial burden can be prohibitive for many potential applications.

Weight Considerations

- RCC’s substantial weight creates various logistical and structural challenges. The typical density of RCC ranges from 2400 to 2500 kg/m³, significantly heavier than alternative building materials.

- This weight factor leads to increased transportation costs, requires more robust formwork, and demands additional attention to foundation design.

- The impact is particularly noticeable in multi-story buildings, where the cumulative weight of RCC elements necessitates larger foundation systems, potentially increasing overall project costs and complexity.

Time-Intensive Construction Process

- The construction timeline for RCC structures is notably longer compared to other building methods. Concrete typically requires 28 days to reach its design strength, and this curing period cannot be significantly shortened without compromising structural integrity.

- The process involves multiple time-consuming stages: reinforcement placement, formwork assembly, concrete pouring, proper curing, and formwork removal.

- This extended construction timeline can lead to increased labor costs and delayed project completion, affecting overall project scheduling and financing.

Reinforcement Corrosion Issues

- One of the most critical long-term concerns in RCC structures is the potential for reinforcement corrosion.

- When moisture and air penetrate the concrete cover, they can initiate corrosion in the steel reinforcement.

- This process is particularly aggressive in coastal areas, industrial zones, or regions with high pollution levels.

- The corrosion can lead to expansion of the steel, causing concrete cracking and spalling, ultimately compromising the structure’s integrity and requiring costly repairs.

Complex Repair Requirements

- When repairs become necessary in RCC structures, they often prove to be both technically challenging and expensive.

- Repairing damaged reinforcement requires careful removal of concrete, treatment or replacement of steel, and specialized restoration techniques.

- The process typically involves sophisticated repair materials, skilled labor, and extensive quality control measures. These repairs can be particularly disruptive in occupied buildings and may require temporary structural support during the repair process.

Shrinkage and Cracking Concerns

- RCC structures are inherently susceptible to various forms of deformation and cracking.

- Shrinkage during curing can reach up to 0.1% of the concrete’s length, while thermal movements cause additional stress. These issues necessitate careful joint placement, appropriate reinforcement design, and proper curing procedures.

- Without adequate attention to these factors, structures may develop unsightly cracks that can compromise both aesthetics and durability, potentially leading to more serious structural issues over time.

Environmental Considerations

- The environmental impact of RCC construction is increasingly becoming a concern in today’s sustainability-focused world.

- Cement production alone accounts for approximately 8% of global CO2 emissions, while steel manufacturing adds significantly to this environmental footprint.

- The process involves extensive energy consumption, resource depletion, and greenhouse gas emissions. These environmental costs are prompting the industry to seek more sustainable alternatives and driving research into eco-friendly construction materials and methods.

Conclusion

Concrete is a strong and durable material widely used in construction.

Reinforced concrete further improves its strength and load-bearing capacity.

It can be molded into different shapes and resists harsh weather conditions.

It may crack and its production causes environmental pollution.

Overall, reinforced concrete is reliable but needs sustainable development.