Transported Soils: Formation and Characteristics

Transported soils, shaped by natural forces like rivers and glaciers, not only influence landscape formation but also impact agricultural productivity. In this article, we will unpack the fascinating formation processes of transported soils and highlight their vital characteristics. Transported soils are formed when rocks undergo weathering at one site, and the resulting particles are relocated to another location. This movement occurs through natural transportation agents, such as gravity, running water, glaciers, and wind.

Types of Transported Soils

Based on the mode of transportation, these soils can be classified into four primary categories:

- Alluvial deposits

- Gravity deposits

- Glacial deposits

- Wind deposits.

Water-Transported Soils

Water-transported soils, also known as alluvial soils, are soils that have been moved and deposited by flowing water in rivers, streams, lakes, or oceans. The key characteristics and types of water-transported soils include:

- Transportation depends on the velocity of water: faster currents carry larger particles like boulders and gravel, while slower currents carry finer particles such as silt and clay.

- When water velocity decreases, coarser particles settle first, followed by finer particles, creating distinct soil deposits.

Water is one of the most influential agents in the transportation and deposition of soil. As it moves, it carries soil particles either in suspension or by rolling and sliding them along the streambed. The size of the particles transported depends largely on the velocity of the water. Swifter currents can carry larger particles, such as boulders and gravel, while slower-moving waters are more likely to transport fine silt and clay.

When the velocity decreases—due to widening, deepening, or a change in direction of the watercourse—coarser particles settle first, while finer ones remain in suspension. This process leads to the formation of various types of deposits, such as alluvial deposits, lacustrine deposits, and marine deposits, each with distinct characteristics.

Alluvial Deposits

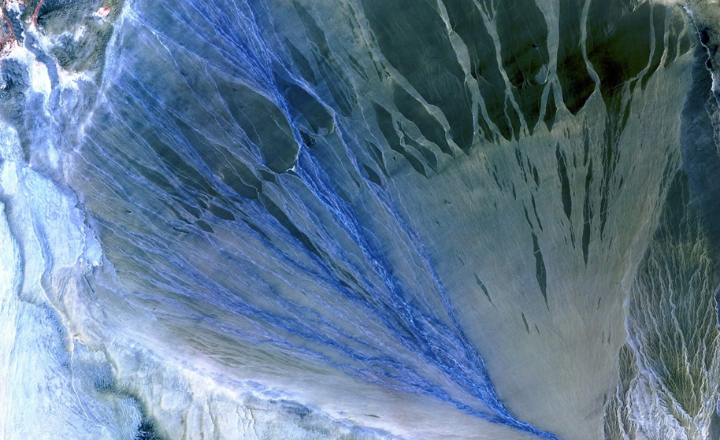

Alluvial deposits are sediments deposited by running water, typically found in riverbeds, floodplains, deltas, and alluvial fans. They form through the erosion, transport, and deposition of materials like gravel, sand, silt, and clay from upstream sources, influenced by factors such as the type of parent rock, climate, and water flow energy.

- Natural Levees: These are formed when rivers overflow their banks during floods. As water slows down, coarser particles like sand and gravel settle near the riverbanks, creating elevated ridges.

- Floodplain Deposits: Finer particles, such as silt and clay, are deposited farther from the river, forming fertile floodplains.

- Alluvial Fans: When a river’s slope decreases suddenly, coarser particles settle into flat, triangular formations known as alluvial fans.

Rivers that meander can create unique features such as oxbow lakes. These are formed when a river changes course, leaving a U-shaped water body that eventually fills with organic and silty deposits.

Lacustrine Deposits

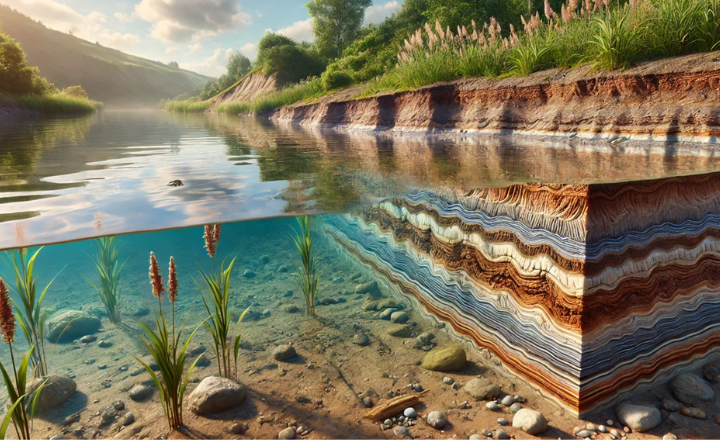

Lacustrine deposits are sedimentary deposits formed in lake environments, typically on the lake bed. These deposits mainly consist of fine-grained sediments such as silts and clays that settle out of still or slow-moving water.

- When rivers flow into lakes, the sudden reduction in velocity causes coarse particles to settle near the lake’s edge, forming lake deltas. Finer particles, like silt and clay, travel further into the lake and settle in quiet waters, forming lacustrine deposits. These deposits are often layered due to seasonal variations and can be weak and compressible, posing challenges for construction.

Marine Deposits

Marine deposits are sediments that accumulate in marine environments such as oceans and seas. These deposits primarily consist of materials transported from land by rivers, wind, and glaciers, as well as sediments formed in situ by biological, chemical, and physical processes.

- Composition: Marine sediments include terrigenous (land-derived) particles like sand, silt, and clay, biogenous materials such as shells and skeletal fragments from marine organisms, hydrogenous minerals formed by chemical precipitation, and cosmogenous particles from space.

- Formation: Fine particles settle slowly from suspension in seawater, often aided by flocculation, where clay and other fine particles bind together to settle faster. Sediments can be deposited on continental shelves, slopes, and deep ocean floors.

- Distribution: Marine deposits are thickest near continental margins due to high sediment input from rivers and thinner near mid-ocean ridges where new ocean crust is formed. Sedimentation rates vary widely depending on location and sediment source.

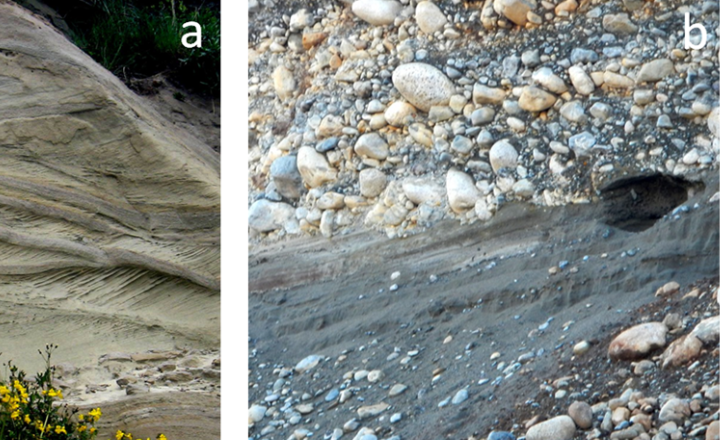

Glaciofluvial Deposits

Glaciofluvial deposits, also known as fluvioglacial deposits, consist of sediments such as boulders, gravel, sand, silt, and clay that originate from glaciers or ice sheets. These sediments are transported, sorted, and deposited by meltwater streams flowing beside, below, or downstream from the ice.

Gravity Deposits

Gravity deposits, or gravity-flow deposits, are sediments transported and deposited primarily by the force of gravity, typically occurring on slopes, underwater continental margins, or in basins. These deposits result from sediment failure, downslope movement, or flows driven by gravity rather than water currents or wind alone.

Examples of Gravity Deposits

Talus Deposits:

- Talus refers to the accumulation of coarse, irregular rock fragments and soil particles at the foot of a cliff.

- It is formed when rocks from higher elevations break apart and slide or fall down under gravitational forces.

- Talus material is typically loose, porous, and coarse-grained, making it a useful source of broken rock pieces and coarse soils for various engineering applications.

Landslide Deposits:

- Landslides occur when large masses of soil and rock are displaced and transported downhill.

- These deposits tend to retain the original characteristics of the materials, as gravity transportation does not significantly alter their composition.

Key Characteristics of Gravity Deposits

- Short Transportation Distance: Gravity limits the movement of materials to relatively short distances, ensuring minimal alteration to their properties.

- Loosely Compacted: Due to the nature of their deposition, these soils are generally loose and porous, posing challenges for construction stability.

- Minimal Sorting: Unlike deposits transported by water or wind, gravity deposits do not undergo sorting, resulting in a mix of particle sizes and shapes.

Gravity deposits play a significant role in understanding soil stability and are crucial in areas prone to landslides or rockfalls. Their engineering applications and challenges vary depending on the specific conditions of the site.

Glacial Deposits

Glacial deposits are sediments and rocks that are transported and deposited by glaciers or ice sheets. These deposits are collectively known as glacial drift and include a wide variety of textures, compositions, and morphologies.

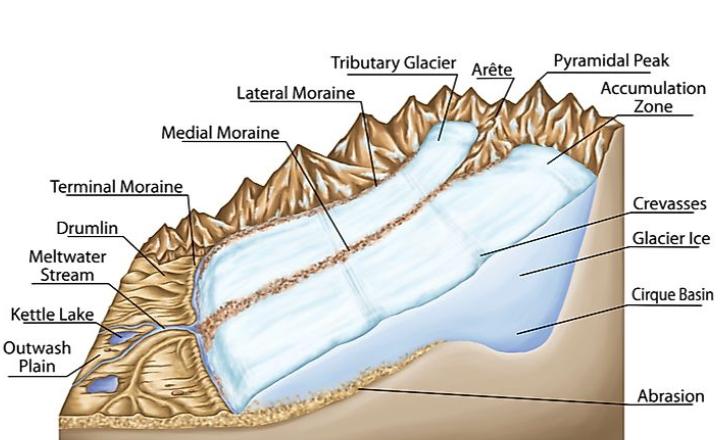

Formation of Glaciers

Glaciers are massive sheets of ice formed by the compaction and re-crystallization of snow over time. These large ice bodies grow and move, scouring the surface and bedrock beneath them. As glaciers advance, they carry a wide range of materials, from fine particles to massive boulders, over long distances. When glaciers melt, they deposit these materials, leading to the formation of glacial deposits.

Types of Glacial Deposits

I. Till

- Definition: Till refers to deposits directly left by melting glaciers. It consists of unsorted mixtures of particles of all sizes, from clay to large boulders.

- Engineering Use: Well-graded and compactable, till often provides high shearing strength, making it suitable for construction materials in certain conditions.

II. Moraines

- Terminal Moraine: Ridges of debris deposited at the glacier’s terminus during melting.

- Ground Moraine: A flat or gently undulating surface formed by till deposited beneath a glacier.

III. Eskers

- Definition: Long, winding ridges of sand, gravel, and boulders deposited by streams flowing within or beneath glaciers.

- Dimensions: Eskers can be 10–30 m high and stretch from 0.5 km to several kilometers in length.

IV. Drumlins

- Definition: Isolated, elongated mounds of glacial debris.

- Dimensions: Drumlins typically range from 10–70 m in height and 200–800 m in length.

V. Erratics

- Definition: Large boulders transported and deposited by glaciers far from their original location.

Vi. Outwash

- Definition: Deposits of sand and gravel carried and stratified by glacial meltwater. These materials are generally sorted and layered.

Engineering Properties of Glacial Deposits

- Heterogeneous Composition: Glacial deposits include a mix of clay, sand, gravel, and boulders. This variability can affect their suitability for construction.

- Compaction: Glacial pressures result in dense deposits, often making them excellent foundation materials, particularly where they contain sand and gravel.

- Challenges with Clay: Deposits high in clay content may pose compressibility and strength issues, making them less ideal for foundations.

Wind Deposits (Aeolian Deposits)

Wind deposits, or aeolian deposits, are sediments transported and deposited by the wind, mainly found in arid and semi-arid regions such as deserts and coastal areas.

Wind, as a natural agent of soil transportation, plays a significant role in arid and semi-arid regions. Wind deposits, also known as aeolian deposits, are formed when soil particles are transported and deposited by wind action. The particle size of these deposits depends on wind velocity and other environmental factors.

Types of Wind Deposits

I. Sand Dunes

- Formation: Sandy particles are moved by wind through rolling or short-distance airborne movement. When the wind loses energy, sand accumulates to form dunes.

- Location: Found in arid deserts, coastal regions, and on the leeward sides of sandy beaches.

- Engineering Use: Sands from dunes can be used in certain construction applications but have limited utility due to their loose and fine nature.

II. Loess

- Definition: Wind-blown silt deposits often mixed with fine sand and clay particles.

- Key Characteristics:

- Low Density: Loess has a loose and porous structure.

- High Vertical Permeability: Facilitates rapid water movement in the vertical direction.

- Cementation: Often includes minerals like calcium carbonate and iron oxide, making it stable when dry but prone to collapse when saturated.

- Location: Prominent in regions such as the Mississippi and Missouri River basins in the USA, northern China, and parts of Europe.

- Engineering Challenges:

- High compressibility and poor bearing capacity when wet.

- Requires special attention for foundation design to prevent collapse or undue settlement.

III. Volcanic Ash

- Definition: Fine igneous rock fragments ejected during volcanic eruptions.

- Properties:

- Light and porous.

- Decomposes quickly into plastic clays.

- Notable Example: The Mt. St. Helens eruption deposited extensive ash layers.

Engineering Considerations for Wind Deposits

- Variability: Aeolian deposits exhibit significant variability in particle size and composition.

- Subsurface Investigation:

- Wind deposits may overlay other soil types, creating heterogeneous subsurface conditions.

- Detailed investigation is crucial for understanding the properties of underlying soils.

- Construction Implications:

- Loess and similar deposits demand careful design to address challenges such as low strength and high compressibility.

- Sands from dunes may require compaction or mixing with other materials for enhanced stability.

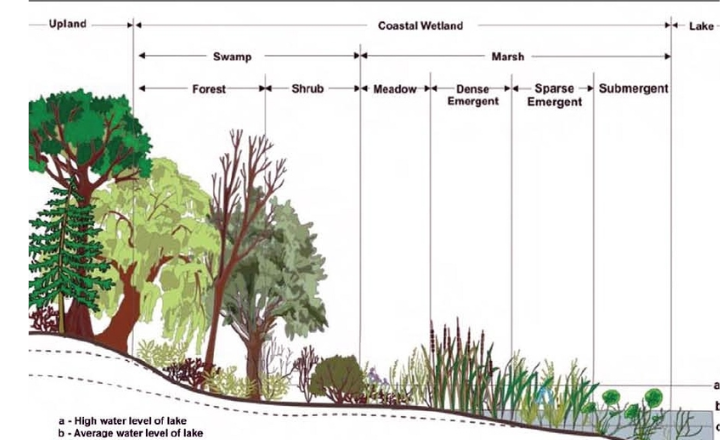

Swamp and Marsh Deposits

- Swamps are wetlands dominated by trees and shrubs with mineral soils that have poor drainage. Swamp deposits consist mainly of mineral sediments mixed with organic matter from decaying vegetation. These deposits form in areas with slow water movement, stagnant pools, or floodplains where organic material accumulates, leading to peat formation in some cases.

- Marshes are wetlands frequently or continually inundated with water and dominated by emergent soft-stemmed vegetation such as grasses, reeds, and sedges. Marsh deposits typically consist of fine-grained sediments such as mud, silt, and clay deposited by tidal or fluvial waters, combined with high organic matter content from marsh vegetation. Mineral sediments usually come from suspended loads deposited during tidal flooding or storm events, while organic matter accumulates from local marsh plants.

Swamp and marsh deposits form in areas with stagnant water and fluctuating water tables where vegetation can thrive. These deposits are characterized by:

- High Organic Content: A significant portion of these soils consists of decomposed or partially decomposed plant material.

- Soft and Compressible Nature: The soils are extremely soft and exhibit high compressibility, making them unsuitable for construction purposes.

- Unpleasant Odor: Organic decomposition often results in a noticeable and unpleasant smell.

The organic accumulation in such areas produces two main types of materials:

- Peat: Partially decomposed plant matter, light in weight, spongy, and highly compressible.

- Muck: Fully decomposed material with similar characteristics to peat but more degraded.

These deposits pose significant challenges for construction and require extensive ground improvement techniques for any engineering applications.

Conclusion

The nature and properties of soil deposits are influenced by their mode of transportation and deposition. This article explored various types of deposits, including:

- Gravity Deposits: Localized and loose deposits like talus.

- Glacial Deposits: Dense and variable soils formed by glaciers, ranging from coarse till to fine outwash materials.

- Wind Deposits: Aeolian soils such as dunes and loess, which exhibit unique characteristics but pose challenges in foundation design.

- Swamp and Marsh Deposits: High organic soils like peat and muck, unsuitable for construction without extensive treatment.

Understanding these deposits is crucial for geotechnical engineers, as soil variability directly impacts construction safety and stability. Comprehensive subsurface investigations and an appreciation of the depositional environment enable the development of effective solutions for foundation and construction challenges.