The Principles of Surveying, a set of essential guidelines that ensure accuracy and reliability in measurements. This article will guide you through these principles, highlighting their significance in various industries, and enabling you to grasp their impact on daily life and infrastructure development.

Working from the Whole to the Part:

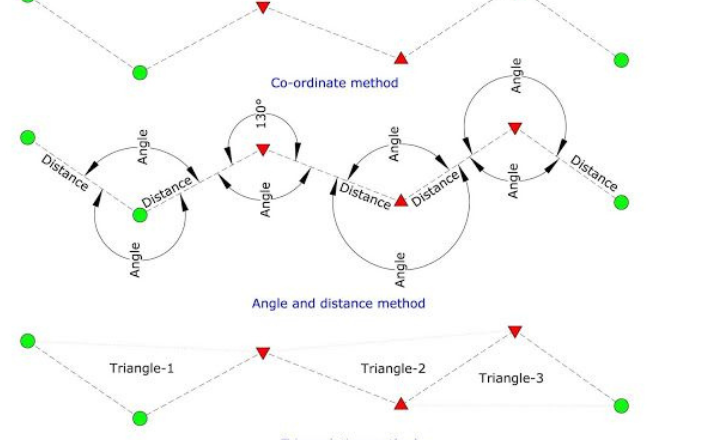

The two primary principles of surveying are:

Working from the whole to the part encourages collaboration among various stakeholders. Engaging architects, engineers, and urban planners from the outset can illuminate complexities often overlooked in individual assessments. This synergy not only enhances the accuracy of the surveying process but also ensures that the final output is more relevant and cohesive, aligning with environmental and social frameworks.

This approach contrasts with working from part to whole, which can lead to error magnification and distortion of the survey scale. In practice, the area is often divided into large triangles, with their vertices surveyed at high accuracy. These are then subdivided into smaller triangles surveyed with less precision.

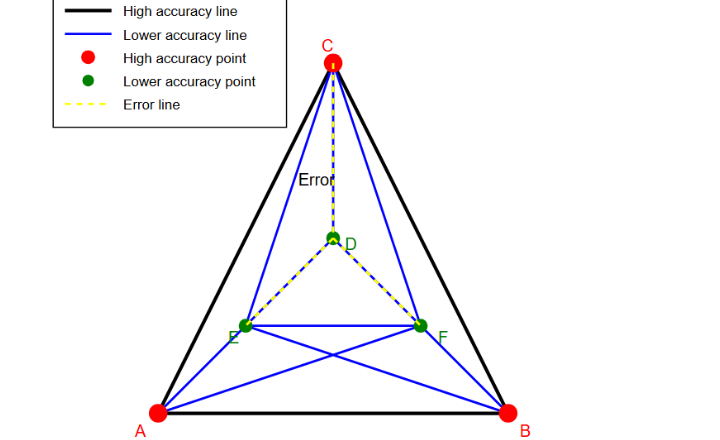

Let’s visualize this concept with a triangulation example:

Locating a Point by at Least Two Measurements

Locating a point using at least two measurements is a foundational concept in the Principles of Surveying, often referred to as triangulation. This method not only enhances accuracy but also provides a robust framework for understanding spatial relationships between points.

This synergy between classic surveying principles and modern technology transforms how we perceive and interact with our environment, showcasing the enduring relevance of accurate measurement in a rapidly evolving world. This fundamental principle ensures the accuracy and reliability of surveying by using multiple measurements to determine a point’s position. It involves selecting two known control points and then using various methods to locate a new point relative to these controls. This redundancy in measurement helps to verify the accuracy of the new point’s position and minimize errors.

Here’s a revised version of the explanation, incorporating the corrections and suggestions:

In this diagram:

- The large triangle ABC represents the primary control network (the “whole”).

- Points A, B, and C are the primary control points, established with high precision.

- The smaller triangles (ACD, BCD, ADF, CEF, AFB) represent the secondary control network (the “parts”).

- Points D, E, and F are secondary control points, established with less precision than A, B, and C.

- Point D was measured with error.

- The yellow dashed lines represent an error associated with point D, affecting the lines CD and DE.

The triangulation process and error localization work as follows:

- Establish primary control points (A, B, C) with high-precision measurements, forming a large triangle.

- Subdivide this large triangle by creating secondary control points (D, E, F) within it.

- Form smaller triangles using both primary and secondary control points.

- Survey details within these smaller triangles.

In this example, an error has occurred triangles (CDE, CDF, and EDF). However, because we’re working from whole to part:

- The error is contained within the small triangles that include point D.

It doesn’t affect the measurements or positions in the other small triangles (AFB, BCF, CEF).

The overall framework (large triangle ABC) remains accurate and unaffected.

This method ensures that:

- The overall framework (large triangle) maintains its high accuracy.

- Errors in establishing secondary points or in detailed surveys are contained within individual, smaller triangles.

- Errors don’t propagate or accumulate beyond the boundaries of the affected small triangle.

By adhering to this principle, surveyors can:

- Maintain high overall accuracy of the entire survey.

- Easily identify and correct localized errors without needing to redo the entire survey.

- Ensure that errors in one part of the survey don’t compromise the accuracy of other parts.

Locating a Point by at Least Two Measurements

Locating a point using at least two measurements is a foundational concept in the Principles of Surveying, often referred to as triangulation. This method not only enhances accuracy but also provides a robust framework for understanding spatial relationships between points.

This synergy between classic surveying principles and modern technology transforms how we perceive and interact with our environment, showcasing the enduring relevance of accurate measurement in a rapidly evolving world. This fundamental principle ensures the accuracy and reliability of surveying by using multiple measurements to determine a point’s position. It involves selecting two known control points and then using various methods to locate a new point relative to these controls. This redundancy in measurement helps to verify the accuracy of the new point’s position and minimize errors.

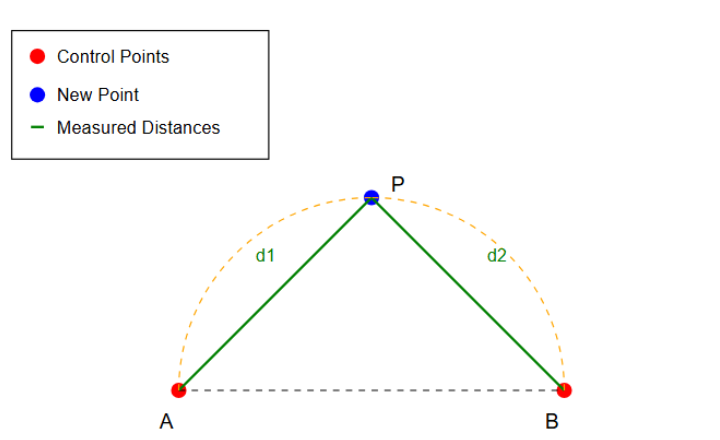

Distance-Distance (DD) Method in Principles of Surveying:

- Measure the distance (d1) from control point A to the new point P.

- Measure the distance (d2) from control point B to the new point P.

- The new point P is located at the intersection of two circles: one centered at A with radius d1, and another centered at B with radius d2.

- Measure the distance (d1) from control point A to the new point P.

- Measure the distance (d2) from control point B to the new point P.

- The new point P is located at the intersection of two circles: one centered at A with radius d1, and another centered at B with radius d2.

Advantages:

- Simple to execute in the field, requiring only distance measurements.

- It can be performed with basic surveying equipment like tapes or electronic distance measurement (EDM) devices.

- Does not require angle measurements, eliminating errors associated with angle observations.

- Effective for short to medium distances, where distance measurements are most accurate.

Limitations:

- Accuracy decreases as the new point moves closer to the line between control points (poor geometry).

- May result in ambiguity when there are two possible intersection points (above and below the baseline).

- Requires clear lines of sight from both control points to the new point.

- Sensitive to errors in distance measurements, particularly when the intersection angle is acute or obtuse.

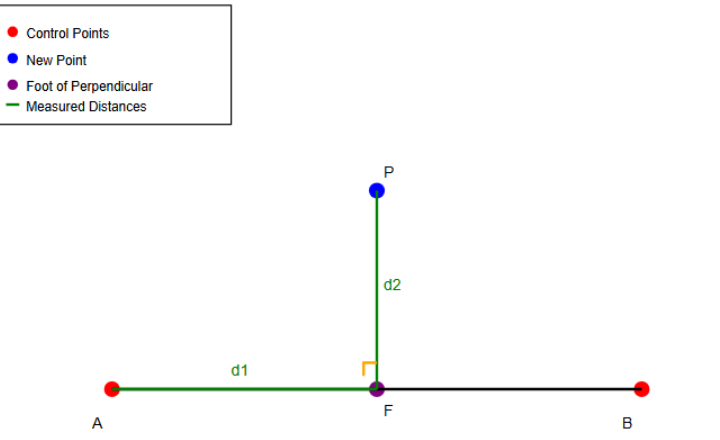

Perpendicular Offset Method:

The Perpendicular Offset Method stands as a cornerstone in the Principles of Surveying, offering a practical approach to map out topographical features accurately. As the surveying landscape evolves, integrating modern tools with traditional techniques like the Perpendicular Offset Method can unlock new dimensions in land assessment and urban design.

- Measure the distance (d1) along the baseline (AB) from control point A to the foot of the perpendicular (F).

- Measure the perpendicular distance (d2) from the foot (F) to the new point (P).

- The new point P is located by these two measurements: distance d1 along AB and perpendicular distance d2 from F to P.

Advantages:

- Useful when the new point is close to the line between control points.

- Efficient for surveying points along linear features (e.g., roads, boundaries).

- It can be accurate when using modern total stations with electronic distance measurement (EDM).

- Simplifies calculations, as it uses basic geometry and right-angle trigonometry.

Limitations:

- Requires accurate right-angle measurement, which can be challenging in the field.

- Accuracy decreases as the perpendicular distance (d2) increases.

- May not be suitable for points far from the baseline.

- Sensitive to errors in establishing the perpendicular direction.

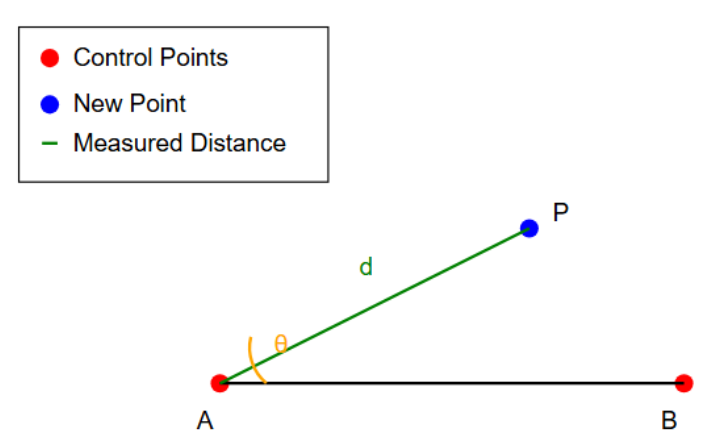

Distance-Angle (Polar) Method:

The Distance-Angle (Polar) Method stands out in the realm of surveying due to its unique application of trigonometric principles.

One of the key advantages of the Distance-Angle Method is its efficiency in open terrain where traditional triangulation might falter. The Distance-Angle Method embodies the essence of the principles of surveying by marrying classic geometric foundations with cutting-edge advancements. For those involved in the surveying profession, understanding this method is crucial, as it opens doors to innovative approaches in project execution and data collection, ultimately shaping the future of land surveying.

- Measure the distance (d) from one control point (A) to the new point (P).

- Measure the angle (θ) between the line connecting the control points (AB) and the line to the new point (AP).

- The new point P is located by these two measurements: distance d and angle θ from the known point A.

Advantages:- Efficient when using a total station or theodolite, which can measure both distances and angles accurately.

- Requires measurements from only one control point, making it useful when one control point is more accessible than others.

- Particularly effective for locating points that are not easily accessible for direct distance measurements from multiple control points.

- Limitations:

- Angle measurement errors can significantly affect accuracy, especially at long distances.

- The impact of angular errors increases proportionally with the distance to the new point.

- Requires a clear line of sight between the control point and the new point.

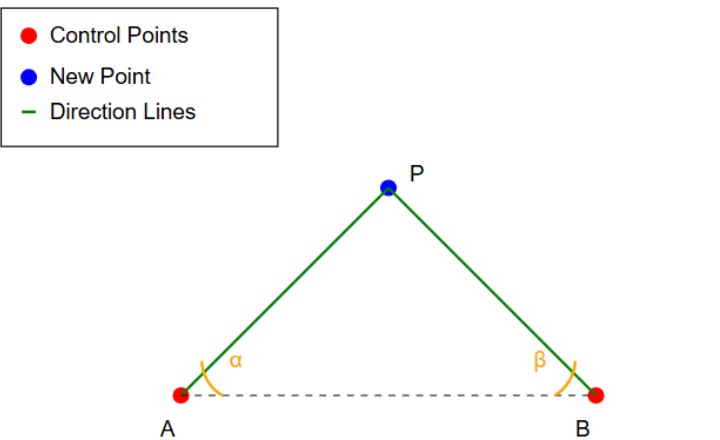

Angle-Angle (Intersection) Method:

The Angle-Angle (Intersection) method, a cornerstone technique in the Principles of Surveying, offers a unique blend of simplicity and precision.

- Measure the angle (α) between the baseline (AB) and the line to the new point (AP) from control point A.

- Measure the angle (β) between the baseline (AB) and the line to the new point (BP) from control point B.

- The new point P is located at the intersection of these two direction lines, determined by angles α and β from the known points A and B, respectively.

- Advantages:

- Useful for locating inaccessible points or points across obstacles.

- Does not require direct distance measurements to the new point.

- It can be performed with angle-measuring instruments like theodolites or total stations.

- Effective for long-distance measurements where direct distance measurement might be less accurate.

- Limitations:

- Accuracy decreases when the intersection angle is very acute (< 30°) or obtuse (> 150°).

- Requires clear lines of sight from both control points to the new point.

- More prone to errors in angle measurement compared to methods that incorporate distance measurements.

- May require additional measurements or control points for verification.

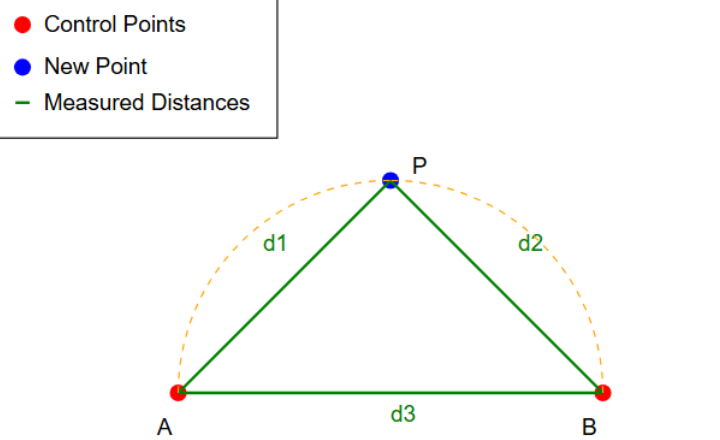

Trilateration:

Trilateration, a cornerstone in the Principles of Surveying, is more than just a method for determining positions; it embodies the intersection of mathematics and technology that shapes our spatial understanding. By calculating distances from three fixed points, this technique leverages the power of geometry to pinpoint a location in two-dimensional or three-dimensional spaces.

- Measure the distance (d1) from control point A to the new point P.

- Measure the distance (d2) from control point B to the new point P.

- Measure the baseline distance (d3) between the two control points A and B.

- The new point P is located by these three distance measurements: d1, d2, and d3, forming a triangle.

Advantages:

- It can be very accurate, especially when using electronic distance measurement (EDM) devices.

- Does not require angle measurements, eliminating errors associated with angle observations.

- Particularly effective for short to medium distances, where EDM devices are most accurate.

- Provides a direct check on measurements, as the three distances must form a valid triangle.

Limitations:

- Requires clear lines of sight between all points (A to P, B to P, and A to B).

- Can be time-consuming, especially if manual distance measurements are used.

- Accuracy may decrease over long distances due to cumulative errors in distance measurements.

- Sensitive to errors in the measured distances, particularly for triangles with poor geometry.

- While the principles of “Working from Whole to Part” and “Locating a Point by at Least Two Measurements” form the core foundation of surveying methodology, they are complemented by several additional principles that ensure the overall quality, reliability, and efficiency of surveying practices. These additional principles work in conjunction with the main concepts to create a comprehensive framework for accurate and dependable surveys. They address various aspects of the surveying process, from consistency in methods to appropriate accuracy levels, further refining the application of the core principles.

Consistency of Work Principles of Surveying

Consistency of work in the context of the Principles of Surveying is not merely about adhering to a routine; it is about cultivating a mindset that prioritizes precision and reliability.

This cyclical nature of learning and applying established principles can lead to increased efficiency and accuracy. As surveyors embrace consistency, they amplify their impact, elevating both the quality of their work and the value they bring to every project. A steadfast commitment to these principles cultivates a legacy of excellence, ultimately shaping the landscapes we live and work in.

Maintaining consistency throughout the surveying process is crucial for ensuring accuracy, reliability, and efficiency. This principle encompasses various aspects of surveying work:

- Uniform Procedures

- Develop and adhere to standardized operating procedures (SOPs) for each type of survey.

- Implement a systematic approach to setting up instruments, taking measurements, and recording data.

- Use consistent methods for stake-out, leveling, and traversing across all project phases.

- Example: Always set up the total station using the same sequence of steps, regardless of the operator.

- Instrument and Method Consistency

- Utilize the same instruments for similar types of measurements throughout a project.

- Maintain consistent instrument settings (e.g., units, coordinate systems, tolerances).

- Apply uniform methods for similar tasks, such as distance measurement or angle reading.

- Example: If using EDM for distance measurement, avoid mixing it with tape measurements for similar applications within the same project.

- Observation Techniques

- Standardize observational methods across all survey sessions and team members.

- Implement consistent techniques for reading instruments, such as always reading angles clockwise.

- Use uniform methods for eliminating or minimizing known errors (e.g., two-face readings for theodolites).

- Example: Always take three readings for crucial angle measurements and use the average value.

- Data Recording and Processing

- Use standardized field books or digital data collectors with consistent formatting.

- Implement uniform coding systems for point numbers, feature codes, and attributes.

- Apply consistent data processing workflows, including software settings and adjustment methods.

- Example: Adopt a standard naming convention for all survey files, such as “ProjectName_Date_SurveyType”.

- Team Training and Protocol Adherence

- Conduct regular training sessions to ensure all team members understand and follow protocols.

- Develop clear, written guidelines for all survey procedures and make them easily accessible.

- Implement a system of checks to ensure protocols are being followed consistently.

- Example: Conduct monthly team meetings to review procedures and address any deviations from protocols.

Independent Check

Independent check is a crucial aspect in the realm of surveying, ensuring that the data collected is not only accurate but also reliable. It acts as a quality control mechanism, where measurements and calculations are scrutinized independently rather than relying solely on initial results.

The principle of independent checking is fundamental to ensuring the reliability and accuracy of survey results. It involves verifying measurements and calculations through multiple, independent means. This principle is crucial for detecting errors, validating results, and maintaining high standards of surveying practice.

- Redundant Measurements

- Employ different methods or instruments for critical measurements.

- Example: Measure a baseline using both EDM and GNSS techniques.

- Repeat measurements at different times or under different conditions.

- Example: Take angle measurements in both face left and face right positions of a theodolite.

- Use overdetermination in survey networks to provide built-in checks.

- Example: In a triangulation network, measure more angles than the minimum required to compute coordinates.

- Employ different methods or instruments for critical measurements.

- Closed-Loop Traverses

- Implement closed traverses to verify both angular and linear measurement accuracy.

- Example: In a polygon traverse, the sum of interior angles should equal (n-2) × 180°, where n is the number of sides.

- Calculate and analyze traverse closures (angular and linear) to assess overall accuracy.

- Use traverse adjustment techniques to distribute errors and improve final results.

- Example: Apply the Bowditch adjustment method to distribute closing errors proportionally.

- Implement closed traverses to verify both angular and linear measurement accuracy.

- Independent Observers

- Assign different surveyors to perform crucial measurements independently.

- Example: Have two team members independently level and read a differential leveling line.

- Rotate responsibilities among team members to avoid consistent bias.

- Compare results from different observers to identify discrepancies or personal errors.

- Assign different surveyors to perform crucial measurements independently.

- Cross-Checking Calculations and Data Entry

- Implement a “four-eyes principle” where calculations are performed and checked by different individuals.

- Use different calculation methods or software to verify results.

- Example: Calculate coordinates using both a spreadsheet and specialized survey software.

- Implement automated data validation checks in survey software or databases.

- Conduct regular audits of data entry processes to ensure accuracy.

- Multiple Control Points and Reference Systems

- Tie surveys into multiple known control points to validate results.

- Use different coordinate systems or datums to cross-check transformations.

- Example: Process GNSS baselines in both local and global coordinate systems.

- Incorporate checks to existing monuments or previously surveyed points.

- Utilize both horizontal and vertical control networks for comprehensive validation.

- Field-to-Finish Verification

- Implement a systematic check between field notes and final drawings or digital models.

- Use automated comparison tools to detect discrepancies between raw data and processed results.

- Conduct site revisits to verify critical measurements or unexpected results.

Benefits of Independent Checks:

- Error Detection: Helps identify blunders, systematic errors, and random errors that might go unnoticed with a single measurement or method.

- Increased Reliability: Multiple independent checks significantly enhance the trustworthiness of survey results.

- Quality Assurance: Provides a robust framework for maintaining high standards in surveying practice.

- Legal and Professional Protection: Thorough checking procedures can provide evidence of due diligence in case of disputes or legal challenges.

- Continuous Improvement: Analyzing discrepancies found during checks can lead to improvements in procedures and methodologies.

- Client Confidence: Demonstrating rigorous checking processes enhances client trust in the survey results.

- Early Problem Detection: Allows for the identification and rectification of issues before they escalate or affect other parts of a project.

- Educational Value: Provides learning opportunities for team members by exposing them to different methods and potential sources of error.

Appropriate Accuracy

The importance of “Appropriate Accuracy” in the “Principles of Surveying” cannot be overstated, particularly in today’s fast-paced development environment.

The principle of Appropriate Accuracy is crucial in surveying for optimizing resources, meeting project requirements, and ensuring the reliability of results. This principle emphasizes the importance of tailoring the survey’s precision to the specific needs of each project or task.

- Precision Assessment

- Conduct a thorough analysis of project requirements before commencing work.

- Example: For a topographic survey, determine if 1cm or 10cm contour intervals are needed.

- Consult with clients, engineers, or project managers to understand the intended use of survey data.

- Review relevant standards, codes, and regulations that may dictate minimum accuracy requirements.

- Example: Check local building codes for required accuracy in boundary surveys.

- Consider future uses of the data to anticipate potential precision needs.

- Conduct a thorough analysis of project requirements before commencing work.

- Instrument and Method Selection

- Choose surveying instruments that match or slightly exceed the required accuracy level.

- Example: Use a total station with 5″ angular accuracy for projects requiring 1:10,000 precision, rather than a 1″ instrument.

- Select appropriate measurement methods based on the accuracy needs.

- Example: Use differential leveling for high-precision elevation determination, but trigonometric leveling for lower precision needs.

- Consider environmental factors that may affect instrument performance.

- Example: In areas with dense tree cover, opt for total stations over GPS for better accuracy.

- Evaluate the trade-offs between different technologies (e.g., LiDAR vs. traditional methods) based on accuracy requirements and project constraints.

- Choose surveying instruments that match or slightly exceed the required accuracy level.

- Project Scale and Data Use Considerations

- Align survey accuracy with the scale of the final deliverables.

- Example: For a 1:500 scale map, ensure horizontal accuracy is within 0.25m (0.5mm at map scale).

- Consider the intended application of the survey data.

- Example: Higher accuracy for legal boundary determination vs. lower accuracy for preliminary site planning.

- Anticipate potential future uses of the data that may require higher accuracy.

- Factor in the propagation of errors in derived products (e.g., volume calculations from surface models).

- Align survey accuracy with the scale of the final deliverables.

- Balancing Accuracy, Time, and Cost

- Conduct a cost-benefit analysis of achieving different accuracy levels.

- Evaluate the time implications of higher accuracy requirements.

- Example: Assess if the additional time for more precise measurements justifies the marginal gain in accuracy.

- Consider the use of newer technologies that may offer higher accuracy at lower cost or time investment.

- Develop tiered accuracy approaches for different aspects of a project to optimize resource allocation.

- Tailored Procedures for Varying Precision Needs

- Implement rigorous procedures for high-precision tasks.

- Example: Use forced centering and multiple sets of angles for high-precision control networks.

- Adopt more efficient methods for lower-precision needs.

- Example: Use RTK GPS for topographic surveys of large, open areas where centimeter-level accuracy is sufficient.

- Develop standardized workflows for different accuracy levels to ensure consistency across projects.

- Train staff on when and how to apply different accuracy standards within a project.

- Implement rigorous procedures for high-precision tasks.

- Accuracy Verification and Reporting

- Implement quality control measures to verify that the achieved accuracy meets project requirements.

- Clearly document and report the accuracy achieved in final deliverables.

- Provide metadata that describes the methods used and the estimated accuracy of different data components.

You may also read about: A Complete Guide to Aggregate Crushing Value Test

Benefits of Appropriate Accuracy:

- Resource Optimization: Ensures efficient use of time, equipment, and personnel by avoiding unnecessary precision.

- Cost-Effectiveness: Balances the cost of survey work with the value it provides to the project.

- Client Satisfaction: Meets client needs without over-delivering on unnecessary precision.

- Reliability: Ensures that the survey results are sufficiently accurate for their intended use.

- Legal Compliance: Meets regulatory and professional standards for accuracy in different types of surveys.

- Flexibility: Allows for tailored approaches to different parts of a project, optimizing overall efficiency.

- Risk Management: Reduces the risk of errors or inadequacies in survey data affecting project outcomes.

- Technological Appropriateness: Encourages the use of the most suitable technology for each task, promoting innovation and efficiency.